The 1980s

Anyone can have Hope

Whatever it Takes

During the 1980s, Hope Cottages made major transitions in its services. The shift went from categorical services to a "whatever it takes" approach. The services became consumer-directed, and Hope sought individually designed support plans instead of the "least restrictive" mentality it worked with before. Hope also established an open-door, no-discharge policy for its consumers. They could use the services when they needed.

Hope wanted to help individuals as independent as possible and wanted the individual to be part of the decision-making process. Hope wanted people to have a say in their future, and for the focus to be on the person—not the problem. To achieve this, Hope geared its services and programs with specific guidelines in mind.

Hope’s Foundational Principles

First, Hope worked on the principle that a person with a developmental disability is capable of learning and growth.

Second, each individual’s needs were identified through an interdisciplinary team—medical, psychological, educational, and social service professionals, along with the individual and their parents or guardians. Together, they created a personalized development plan.

Third, following Wolf Wolfensburger’s philosophy, Hope aimed to provide a normalizing environment—living conditions at least as good as those of the average citizen.

Finally, Hope believed people should live with as few restrictions as possible while still receiving necessary support, fostering growth and independence.

These principles guided the Individual Program Plan, continuously reviewed and tailored to each person’s progress.

By 1982, Hope celebrated 15 years of service, offering various living options, including three 10-bed Intermediate Care Facilities (ICFs) funded through Medicaid. These homes exceeded state and federal standards, providing 24-hour nursing care in a home-like environment, and consistently earned excellent reviews from the Medicaid Division throughout the 1980s.

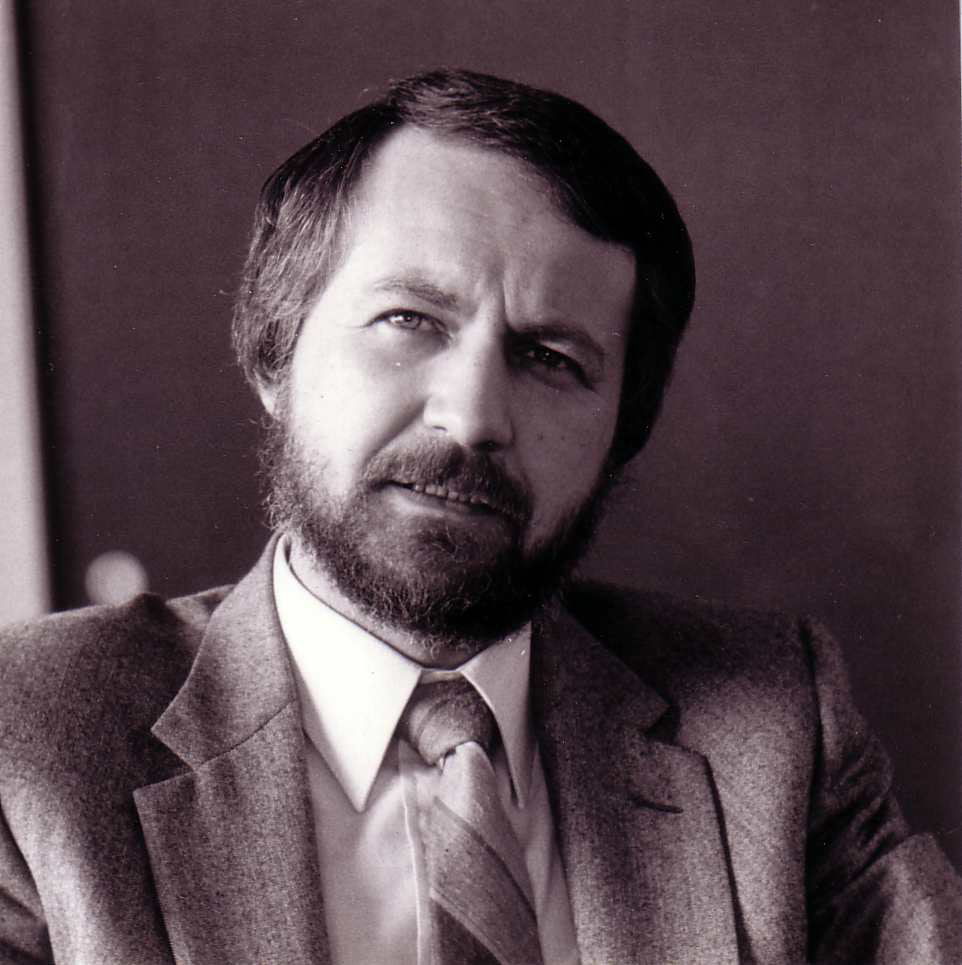

Steve Lesko

and the Legacy of Hope

When Lesko first took over as Executive Director, his major effort was focused on transitioning Hope into a real home environment. He wanted to reject the "home-like" concept Hope had been using. A home is either a home or it isn't, Lesko believed. Home-like is not a home.

Home environments meant Hope needed to provide decent furniture—not the government surplus furniture in most of Hope's houses at the time—as well as privacy and space for individuals. Lesko wanted to get rid of anything related to institutional-style services.

This led Hope toward a major reorganization. In the past, Hope offered consumer categorical services, a menu of services that people could select from. Only, that did not leave much room for individualization. Under Lesko's leadership, Hope began offering "wrap-around services." The person would decide what they wanted and Hope would build the services to "wrap around" those desires and dreams.

Thus began Hope's mission of helping individuals make decisions that would affect their lives. The power was, and continues to be, in the hands of the individual.

This philosophy drove Lesko and Hope's Deputy Executive Director, Roy Scheller. For decades, the pair led Hope's outreach across the state through Rural Support Services and molding Hope's services toward individual dreams.

Scheller, who had been Deputy Executive Director since 1984, helped Hope incorporate the concept of dreams into new services. He and Lesko worked on a new program called Dream-Based Planning.

Scheller, who had been Deputy Executive Director since 1984, helped Hope incorporate the concept of dreams into new services. He and Lesko worked on a new program called Dream-Based Planning.

Based on his personal expertise and commitment to dreams, Scheller paved the way for the creation of an expansive internship program. The program went international and included such universities as Waterford Institute of Technology in Ireland and the State University of New York, Plattsburgh.

Scheller also stressed the importance of culturally appropriate service delivery in remote areas in Alaska. He and Lesko collaborated in the development of the regional centers and direct service provision in small communities. Their shared conviction in the wisdom of Alaska Native elders, the village, and traditions created a foundation for new service delivery designed through specific cultures.

The duo had a firm belief in the organization's values, which created a solid foundation for the future. As for the future of those supported by Hope, Lesko said he believed that it could be whatever they can dream.

Independent Living

In March of 1986, two new five-bed homes—Arlene and Juliana—were opened in a South Anchorage neighborhood. While these two homes still met the strict federal guidelines, much thought and care went into providing the most comfortable and functional design possible. Also, with only five people per home, there was a better staff-to-individual ratio.

A second living option Hope offered was the group home. In 1982, the Group Home Services Program contained 14 homes—10 for adults and four for children. Each children's home provided developmental supports for four children between the ages of five and 18. A live-in program coordinator ensured that children were surrounded with a family-like environment. The developmental program helped each child learn to function in an age-appropriate manner and supported children who needed specialized support to develop daily living skills.

Children who did not require a group-home setting were placed with foster families, a program which began in 1976. All potential foster families were recruited through Hope and were licensed by the Alaska Division of Social Services. However, by the mid-1980s, Hope had made a philosophical decision to close the children's group homes. Children belonged in their natural home if at all possible. If not, they should be with a loving foster family, not in a group home. This shift in philosophy pioneered the way for the Family Support Program in the early 1990s.

The 10 adult homes had four to six individuals each who were aged 18 and older. In addition to a live-in program coordinator, additional staff worked with individuals as adult role models. The training programs these staff provided were designed to maximize everyone's potential to live independently in their home and community. Hope believed that once independent living skills were mastered, people would leave the group home to begin a more independent lifestyle.

During the 1980s, Hope began using houses in residential neighborhoods for group living. The homes are spread throughout Anchorage to encompass full inclusion in the community. People in Hope's Independent Living Program learn daily living skills, such as shopping, cooking, and mobility within their community.

An independent lifestyle was offered through three of Hope's options. The first step in independent living was the Apartment Cluster program. Hope chose large apartment complexes so that the participating individuals would be able to interact with a larger environment. Hope purchased two apartment buildings of six apartments each on Timothy Street, located in a neighborhood in southwest Anchorage. Each building was staffed with a program coordinator who assisted the people living there.

The next step toward independent living was the co-residential program, in which two people lived together in an apartment of their choice in the Anchorage area. Hope helped people find compatible roommates by matching complementary skills, and together they formed a successful living unit. Hope staff visited each apartment several times a week to provide support and independent living training. The final step was the semi-independent living program, which provided support on an as-needed basis. However, in this program, individuals would call and make appointments to see staff at Hope's business offices or at their home when necessary. At this point, people could either continue to rent a place or purchase their own home. Hope staff would continue contact with the individual and would only intervene if requested or for health and safety reasons. Hope desired this ultimate goal for all individuals who wished to live independently. Otherwise, Hope supported people on whatever level they needed in order to be as independent as possible.

Special services also developed during the 1980s marked major transitions for Hope. First, people could move from home-like residences to actual homes and from duplexes and cluster living arrangements to regular home environments. This meant they were actually living in a community. Through these living arrangements, individuals learned to rely less on Hope's staff and more on the community they lived in for day-to-day tasks.

Home Ownership

For many individuals who experience a disability, the opportunity to become a homeowner is life-changing. Homeownership represents stability, pride, and a sense of belonging in one's community. Owning a home allows people to make their own choices about how and where they live—whether that means decorating their space to reflect their personality, choosing their neighborhood, or setting their own daily routines.

Hope recognizes that supporting people in pursuing homeownership—when it is their goal—is a key step toward full inclusion and autonomy. Through partnerships with lenders, housing programs, and advocacy for more accessible financing, Hope ensures that people who want to purchase a home have the same opportunities as anyone else. This not only increases personal independence but also builds long-term security, helping them build roots in their community.

One of the first people Hope supported to purchase her own condominium was named Twan. Purchasing her home increased Twan's independence dramatically; her reliance on Hope became almost non-existent.

Autism and Dual Diagnosis

While the 1980s presented more living options available to the individuals supported by Hope, this decade also marked an increase in the array of services available to all Alaskans with developmental disabilities. One area into which Hope expanded was the provision of services to individuals who are autistic, which had long been neglected by Alaska's social services.

In 1982, Hope received a grant from the Municipality of Anchorage to work with the parents of autistic children in creating an assessment center. The center would offer natural home training, support, and developmental services for individuals with autism. Hope also used these funds to establish a resource library on autism and behavioral disorders, which was accessible to the public.

In 1984, two new group homes leased by Hope were specified for individuals with autism. These two homes were the first residential programs of this kind in Alaska. Within a decade, Hope desegregated these homes and incorporated people with autism into its regular residential programs. Hope had become instrumental in providing support to another segment of Alaskans who experienced developmental disabilities.

Hope noticed another group Alaska's social services neglected—people who had both a developmental disability and behavioral challenges. In 1985, Hope received a grant from the State of Alaska to open the first ever dual-diagnosis group home. Four individuals were supported in this home. It was such a success, it pioneered the future development of mental health services at Hope.

Key Campaign

In 1986, Hope was a major organizer of a tradition that remains at the heart of its values and community outreach. Late in the year, community programs across the state received a 16.22% budget cut. While the organization made it through, it realized the cut in funding had a serious effect on service delivery and on Hope's ability to reach people on their waitlist. Something needed to be done.

Hope was a founder of the Key Campaign of Alaska and invited anyone across Alaska who cared about the future of services for the developmentally disabled to join. The Key Campaign's core is two days in Juneau, usually in late February or early March each year. The campaign participates in a legislative hearing, meets with the governor, visits legislators, hosts a dinner, and has a candlelight vigil to remember people on the waitlist.

The goal of the Key Campaign is awareness, which has helped Hope and other service agencies maintain funding without further cuts. But the Key Campaign has become a statewide way for parents and families of the developmentally disabled to realize they aren't alone. Over a decade later, Hope was a founder of the Key Coalition of Alaska, which now operations the Key Campaign. This organization is a statewide coalition of consumers, families, providers, and advocates for developmental disabilities.

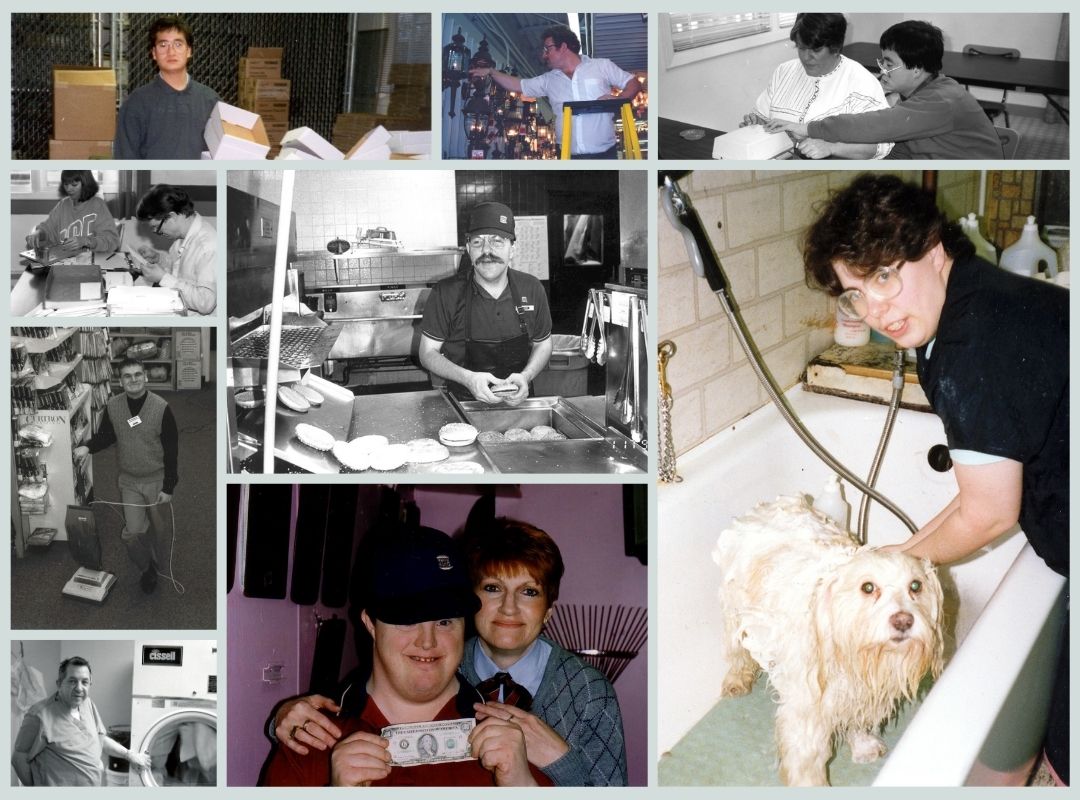

Supported Employment

The mid-1980s saw Hope's services expand beyond residential concerns and into vocational needs. For individuals to be independent and integrated in their communities, they needed vocational training. Hope wanted to provide people with work or career training opportunities. Hope was challenged because vocational and employment support for individuals with severe physical and developmental disabilities were unavailable. The vocational assistance evolved from a sheltered workshop program to a supported employment concept, which offered individuals job placement in the community.

Hope established a workshop to train individuals in vocational skills. But not all—especially the more medically and physically restricted—were able to find employment opportunities in the community. Hope realized that they had to expand again to create employment opportunities for these individuals. Under the guidance of a new program—Supported Employment Services—vocational training and gainful employment was encouraged among this population.

By the end of the 1980s, there were 44 adults receiving services from Supported Employment Services in a variety of job settings. These included independent placement in the community, group placement as work crews, as well as a sheltered workshop to enhance vocational skills. Wages were paid at or above minimum wage, which resulted, for some, in partial reduction of dependency on public programs for income support. The people employed were able to develop their skills, build a more positive self-image, and integrate into their community.

As the Supported Employment Program expanded, so did the job opportunities. Hope's consumers have been offered jobs in offices, janitorial positions, hardware stores, restaurants, print shops, animal care, and more.

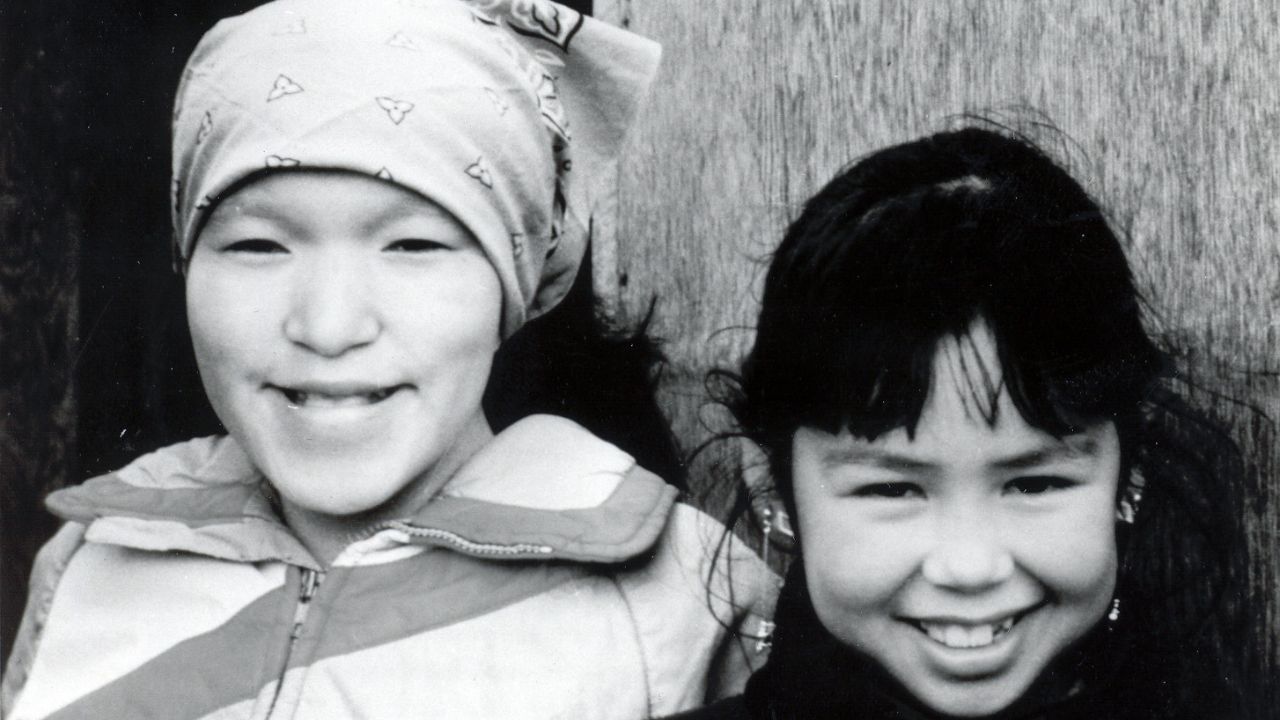

Rural Supports and Services

Under the direction of Steve Lesko, Hope realized it needed to look beyond the Anchorage community and provide better support to individuals who lived in rural areas or who had been forced to relocate to Anchorage for services. In 1986, Hope began supporting 15 individuals in the Nome, Dillingham, and Kotzebue areas through a grant received from the State of Alaska.

|

|

The Rural Family Support Services Program allowed individuals—who had originally come to Anchorage for services—the opportunity to return to their homes. The program also wanted to prevent people in rural environments from having to move to Anchorage to receive services. Hope initially offered these communities the options of shared-care and in-home services. This provided support directly to the families. Former employee, Robin Ynacay-Nye, was the major architect of Hope's rural service delivery and family support expansion.

The geographic distance between communities, unstable or severe weather conditions, limited transportation options, as well as the lack of local services presented challenges in Hope's statewide outreach. Hope realized that successfully implementing these rural services would require an innovative approach. Hope also wanted to involve as much of the community as possible. In each rural area of services, Hope established a Community Resource Team. This team, made up of community members, provided advisory and support roles for the agency.

Looking Ahead

By the end of the 1980s, Hope provided support to 200 Alaskans of all ages in the Anchorage and Matanuska areas as well as the Bristol Bay Region. Forty-four of the people were also receiving supported employment services. Hope had significantly expanded its support services, and staff, and managed an annual budget of almost $8 million.

By the end of the decade, support to individuals with developmental disabilities had dramatically refocused at Hope and throughout Alaska. Children and adults were advocating for themselves and planning their futures.