The 1960s

Finding Hope in Alaska

Nancy Stuart Johnson, Founder of Hope

Nancy Stuart Johnson came to Alaska, the Last Frontier, with a pioneering spirit. She headed north from Florida with her husband, Don, and their four children in 1967. Nancy moved to Circle in October, just weeks before the Tanana and the Chena rivers flooded. A newcomer and barely settled in her new home, Nancy did not let that keep her from helping in the community during the disaster. Day care centers were set up around town to take care of children whose parents were busy fighting the flood. But Nancy recognized that some of the children needed extra care.

Nancy worked with children with developmental disabilities in Florida, but only as a volunteer without any real training. That was enough. Her interest was piqued and she acted. Nancy went to the Department of Health and offered her services. Unwittingly, she had tapped a serious need in the community.

Hope Cottage Incorporated

The Department of Health quickly put a four-year-girl named Nora in Nancy's care. Nora, in her short life, had lived in 26 foster homes. She was nonverbal, she ate with her hands, and she was not toilet trained. Nancy and her husband became Nora's 27th set of foster parents.

Six months later, Don found a job with a local television station and the Stuarts moved to Anchorage, bringing Nora with them.

The Stuarts received a second foster child, Mikey, an orphan who was sent to Alaska Psychiatric Institute from the Baby Louise Haven institution in Oregon. Within a year's time, the Stuarts moved into a larger five-bedroom home on Sunrise Drive.

This move was necessary—more kids were on the way. By August 1968, the Stuarts were caring for 14 foster children with special needs.

"[We would take] any child with a mental or physical handicap, any child who wouldn't fit into a more relaxed setting," Nancy said. "It was just the kids who nobody else would have."

The State of Alaska informed Nancy that she needed to apply for an institutional license. She was caring for too many children for her Sunrise home to be considered a child-care home. "That was the last thing I wanted to be. Even though we had 14 kids in the home, it was in a neighborhood in the community, just like anybody else's house," Nancy said. "The kids went to the same school across the street. The word 'institution' made me shudder; that was what I didn't want."

Nancy needed to choose a name for her new professional organization. She decided on Hope Cottage—Cottage implied a home-like environment, and Hope referred to the immeasurable amount of hope she had for the children. Equally important to Nancy, the name and services she pioneered would never reflect an institutional environment. Nancy's goal for Hope Cottage was to provide kids a home and integrate them into the community.

Hope Cottage incorporated in October 1968, and the organization moved to a new level. Nancy knew nothing about administratively running a children's home. At the time, she had a high school diploma and no formal business experience.

By law, as a non-profit agency, Hope was required to have a board of directors with a minimum of five members. Nancy quickly assembled a board using connections she had since establishing her foster-care family. She looked to people who could help and guide her. Whether needing loans to pay the employees when the state checks did not come in on time or administrative assistance, she found board members she could always count on.

About this time, Nancy was becoming financially, physically, and emotionally overwhelmed. The State suggested she and her family move into another house and hire house parents for the Sunrise home. The Stuarts, moved and within three weeks, seven more children moved in with them.

Because of Nancy's unique situation, the State referred to her operations as a specialized group home. She received $174 per child each month—the same rate as foster care. She also had a contract for services from the Division of Public Welfare and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which supervised children from Bush communities placed in her care.

Nancy also successfully contracted with the State's Division of Mental Health—the area of government entrusted with funding for people with developmental disabilities.

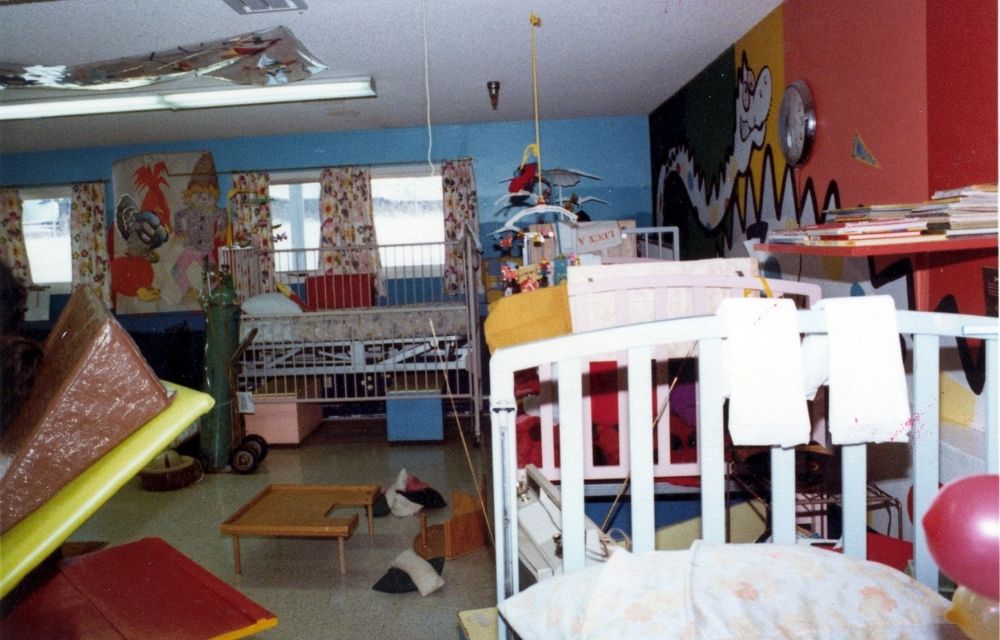

Nancy expanded Hope by opening a new home on St. Elias Street. Six boys, ranging from eight to 14 years old, lived there with their house parents, Corky and Fred Taylor. Nancy also opened a home on Dorbrandt Streeth, affectionately referred to as the babies' cottage. It was funded through a special contract with the Division of Mental Health, with stipulations that its residents be non-ambulatory and have an IQ under 30.

Nancy's quest to keep people out of institutions was realized, but she continued to have financial difficulties. Her various contracts were based on reimbursement for services, which always resulted in cash-flow problems. This forced Nancy to do most of the work on her own. She maintained the minimum staff-to-consumer ratio and creatively used volunteers to fill the gaps. Nancy's contracts, with the permission of her consulting doctors, allowed her to perform various medical procedures. This factor, coupled with the assistance of nursing students from the University of Alaska, pulled her through. Eventually, Nancy was able to hire licensed nurses, but registered nurses were always beyond her financial capability. But in 1971, when Hope Park Cottage was built, Vivian Kurtz, a registered nurse, was hired as head of the home, with three registered nurses on her staff.

These early years in Hope's development were the most memorable for Nancy, but they also took their toll on her health. It was normal for Nancy to fill in when an employee could not show up, and often she would work 20-hour days between the homes.

By the end of 1969, Nancy had 14 children at Sunrise, 16 at Dorbrandt, and six at St. Elias.

Hope Park and the Bacon Family

Before Hope, developmentally disabled children were institutionalized out of state. Most of their parents lived in remote parts of Alaska, making regular communication and contact difficult or almost impossible. The lack of communication also meant parents had little knowledge of their children's status or progress, and the institutions were not always helpful.

Hope was able to bring many of these children back to Anchorage, and Nancy welcomed involvement from their parents. But geography still created an obstacle. The majority of parents living in Bush communities could not afford trips to Anchorage. When they did make it to town, the trip from a remote village to Alaska's biggest city was total culture shock. Aside from being reunited with their children, Nancy said the main thing they wanted to do when they were in town was go to JC Penney's and rise the escalator.

Tom and LaNelle Bacon were some of the first parents involved with Hope. They were motivated to make sure Hope was a success because of their daughter, Shawneen.

Shawneen is Tom and LaNelle's only child. She was born on May 17, 1969, with multiple physical and developmental disabilities. Doctors told the Bacons she would not survive beyond six months.

Tom and LaNelle were instructed to make Shawneen's life as comfortable as possible and to wait for the inevitable. But the Bacons were not willing to give up on their daughter. They cared for her around the clock, exhausting themselves in the process.

Shawneen's disabilities were too severe for her to be sent to Harborview, the institution in Valdez. She managed to get on a waiting list to remain in Alaska, avoiding the Baby Louise Haven institution in Oregon.

When Shawneen was five months old, her doctor, Helen Whaley, noticed LaNelle and Tom's extreme exhaustion. Dr. Whaley told the Bacons about Hope's services and Nancy, who might be able to provide respite care for Shawneen.

LaNelle vividely remembers her first encounter with Nancy and Hope. They were reluctant, but they

bundled Shawneen up on Sunday, October 12, 1969, and set off to Nancy's Dorbrandt Cottage. "We didn't know what to expect," LaNelle said." But [the house] had this great big country kitchen and on the stove she was cooking up these wonderful southern beans. And there was just something wonderful about that pot of beans that really called to me. They just smelled wonderful."

The physical setup of the house, although makeshift, also appeared homey and comfortable. The Bacons had confidence in Nancy's ability to care for Shawneen, and they placed her with Hope the following day. LaNelle also recognized Nancy's serious financial problems and lack of business organization, so she volunteered her services as a bookkeeper. She could remain close to Shawneen while helping Nancy.

Shawneen entered Hope only a month before Bob Halcro assumed control of the board. Soon after, with the closing of Dorbrandt in 1969, Shawneen moved to the Alaska Psychiatric Institute and eventually into the new facility, Hope Park.

Tom and LaNelle remained active participants in Hope, forming a parents' group that helped raise funds for another new house, Ocean Park. When Ocean was completed, Shawneen moved in. Eventually, two five-bed homes were built in 1986, and Shawneen came to reside in one of them. These homes were called Intermediate Care Facilities for the Mentally Retarded and were funded through Medicaid.

Tom, LaNelle, and Shawneen were also at the forefront of Hope's groundbreaking move toward decertifying its intermediate care facilities and recertifying them as assisted living homes.

Shawneen and her housemate were some of the first in the Roadmaps project, developed in the mid-90s, to move into their chosen home, close to Tom and LaNelle. In 2004, Shawneen turned 35 years old—a far cry from the original six months her doctors predicted at birth. She lives with her housemate, Dana, whom she has grown up with since entering Hope. Tom and LaNelle look at themselves—Shawneen, Dana, and staff—as one big happy family.