The 1970s

Building Hope

A Turning Point for Hope

Nancy managed to keep Hope running, but barely. By October 1969, her situation was reaching a crisis point. Her debt was accumulating and there was no prospect of stabilizing her finances. The plight became public when she searched for contributions.

Inaction, however, was not in Halcro's vocabulary.

When Halcro arrived at his meeting, he started telling people what he had just seen. He arranged to show people the Dorbrandt house. In following days, he expanded his roundup of community leaders to include both friends and business associates. He eventually called a meeting to organize these people, and attendees included bankers, lawyers, a journalist, members of the local Republican committee, accountants, and other prominent business leaders.

Following the meeting, a group was formed to quickly develop a plan of action. They established a new board, incorporating Nancy's original members, but bulking it up with local business experts. Members included Halcro as Chairman, Ray Elliss, Halcro's accountant, as treasurer, local judge Connie Occhipinti, and Marjorie Fitzpatrick, as well as Nancy's original group. Also included were people who had been involved with Nancy, lawyers Marvin Frankel and Martin Farrell. This group immediately began working on pulling Nancy out of debt.

One of their first concerns was money for food. When Carrs grocery stores agreed to give Hope a $600 loan for food, Halcro expanded his scope and decided to start a fundraising effort. In a letter dated November 11, 1969, to Ed Hansen, head of Hope's fundraising committee, Halcro outlined his goals for Hope and his ideas to raise money through the coming year. "We have established a goal of $50,000 for Hope Cottage. This should enable us to get the wolf away from our door, budget Hope Cottage for the year 1970, and enable us to have a little cushion."

In this letter, Halcro stressed the urgency required in beginning this effort and requested prompt action. His ideas included a tour of the Harlem Clowns basketball group in March 1970; a silver tea party at the home of board member Bill Myers and organized by Marjorie Fitzpatrick and her Hope Ladies Auxiliary in January 1970; and the Walk for Hope, an event to attract the whole community, to be held on Saturday, May 2, 1970. Halcro set in motion a plan for Hope's financial establishment.

In this letter, Halcro stressed the urgency required in beginning this effort and requested prompt action. His ideas included a tour of the Harlem Clowns basketball group in March 1970; a silver tea party at the home of board member Bill Myers and organized by Marjorie Fitzpatrick and her Hope Ladies Auxiliary in January 1970; and the Walk for Hope, an event to attract the whole community, to be held on Saturday, May 2, 1970. Halcro set in motion a plan for Hope's financial establishment.

The December after Halcro set up his new board, Nancy suffered a nervous breakdown and removed herself from further participation with Hope. She and her family moved to Kodiak and eight months later left Alaska altogether. Her two-and-a-half year endeavor physically and mentally exhausted her. But Nancy's heroic efforts and the extraordinary service that she established would last.

John Moletti was named the first president of the new board, but Halcro remained the driving force. Halcro eventually assumed the presidency in March 1970 and the effort was officially in his hands.

The First Full Decade of Hope

By 1970, Hope was developing a positive reputation in the community; it was recognized as a valid, trustworthy organization. This status had to be maintained through changes in Hope's structure and policies.

As Executive Director, Kent's first success was moving the children from the Koutsky Unit at Alaska Psychiatric Institute to Hope Park. By 1972, Hope had also opened a large group home for adults, located on Bering Street. It was a converted two-story four-plex that became home to 10 women and 14 men, with the women and men living on separate floors, each supervised by live-in house parents.

The Bering house marked Hope's first step in providing community-based residential services for adults, offering an alternative to institutional living. While large group settings weren’t ideal philosophically or operationally, within three years, all residents transitioned into apartments in Anchorage. From that point forward, when Hope expanded its group-home program, adults moved directly into apartments or single-family homes with a live-in staff person.

By the mid-1970s, Hope focused on reducing the number of people in group homes, both for children and adults. For children, the goal was to mirror a family environment—with an appropriate age and gender mix, and married, live-in staff serving as parental figures. For adults, live-in staff served as friends and role models, helping residents develop independence. Across all homes, the primary goal was to build independent living skills.

The Walk for Hope

Today, when Bob Halcro's name is mentioned, people automatically refer to his fundraising brainchild—the Walk for Hope

Halcro's idea was inspired by a nationwide benefit for the struggling West African state Biafra held in 1969. Biafra, a southern area in Nigeria, had been fighting for their independence. All around the United States people organized to raise money to aid the Biafrans. Various "Walks for Biafra" were staged, and Anchorage successfully participated in this effort.

Halcro realized if the community was willing to be generous to a foreign cause, they might be equally generous to a cause closer to home. Alaska and its people appeared to have a vast potential for charity. He decided to act on his hunch and began organizing a 'Walk for Hope.'

Halcro decided to hold this walk on the first Saturday of May in 1970. Spring in Anchorage would encourage people to get outside. Five months before the Walk, planning began; over a hundred local students and adults stopped by the Walk for Hope headquarters on Fifth Avenue and C Street the first weekend of the new year to find out about volunteer positions for organizing the Walk. Roger Lewis volunteered his services as the student chairman and, in an article in the Anchorage Times, explained his motives for helping. He cited the financial situation at Hope, but also mentioned 66 children at Morningside Hospital in Oregon who needed to come home to Alaska, and the 1,200 to 1,500 other special needs children still living throughout Alaska who received no care at all. All of these children could benefit from the success of Hope. Lewis encouraged the community to volunteer, "Your help is their hope."

Not everyone in Anchorage was happy with Halcro's idea, however, Because of the Walk for Biafra's success, a group of local students were trying to repeat the effort in 1970. This time, they were planning to give 55% of the proceeds to charitable organizations around the United States and in foreign countries and retain 55% for distribution among charitable organizations in Alaska. They took issue with Halcro's plan that Hope's event would only support Hope Cottage and not their idea of spreading the wealth. After much dissension and power play heightened by the media, the students expressed their frustration in dealing with the older generation.

For a while, two separate walks were being organized, and the community took sides. Some groups made Halcro a personal target, claiming that he was superseding the noble efforts of these students, causing their event to fail.

The Anchorage Times was particularly supportive of the students and wrote articles and editorials on their behalf. Halcro responded to these attacks by asserting that no one group had a claim over the charitable donations of the city, and he took the opportunity to inform the community further about Hope and its dilemma. He also argues that Hope was a local organization, deserving of the community's support, not their hostility.

The controversy eventually abated, and the Walk for Hope went on as planned. Organizing the Walk was a tremendous effort, and undertaken entirely by volunteers. A considerable amount of time was spent developing the route. Halcro wanted the Walk to be 31 miles.

Planning a 31-mile walk was not a simple task. At that time, Anchorage's extensive bike trails had not been developed. Providing a safe route was a difficult puzzle for the organizers to solve. Many days were spent driving around Anchorage determining mileage and trying to space checkpoints. The logistics involved were staggering. Nothing of this magnitude had been attempted in Anchorage before, and organizers had to rely on common sense to foresee potential problems.

In addition to meeting the challenges of the physical layout of the route, providing food for the walkers was nother issue. Thousands of peanut butter sandwiches were made and frozen in anticipation of the Walk day. later, this solution to the food dilemma stirred funny memories with the early race organizers as they recalled eating a semi-frozen peanut butter sandwich after walking 31 miles.

Halcro's Walk for Hope promotion included inviting the schoolchildren to participate by organizing registration in the schools and working with the Anchorage School District. Halcro wanted children to help other children through leadership and unselfish motivation. The plan worked, children signed up, and the Walk became the cool thing to do every spring. The participation of schoolchildren has provided an important backbone to the Walk ever since.

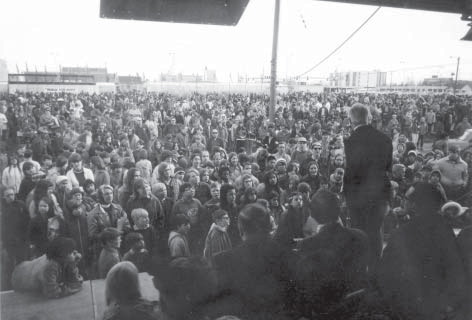

As the Walk approached, people were gearing up and soliciting sponsors citywide. The organizers were surprised and pleased at the response. Thousands of people, many of them children, had volunteered to walk. The Anchorage Times and the Anchorage Daily News both lent their efforts to promote the cuase. On May 1, the Times published a front-page article claiming the possibility that 3,500 people—an impressive chunk of Anchorage—were walking the following day.

People were also using their creativity to raise funds. Jack Griffis, owner of D&J Airlines at Merrill Field, gave rides in a nine-seat twin Beech airplane all day Saturday. All of his proceeds were donated to Hope. On the Sunday after the Walk, the spirit continued. The Alaska Motorcycle Association planned a 'Ride for Hope,' a motorcycle race at th ePalmer fairgrounds, and donated 50% of the proceeds to Hope. And to satisfy late-night hunger, Chuck Merillat, owner of two Pizza Huts in Anchorage, staged a 'pizza smorgasbord.' He offered all types of pizza for $2 per person, and donated 20% of his profits to Hope. He also issued 'Pizza Bucks' worth $1 toward the price of a pizza to each person who completed the Walk.

The Walk began with opening ceremonies and registration at 6am on the Park Strip between C and E Streets downtown. The actual walking began an hour later and registration was open until noon, in case people wanted a later start. Police and emergency medical services ensured the safety of the walkers throughout the course. Official cars patrolled the route to pick up people who could not finish. The Last Frontier Cycle Club acted as crossing guards at major intersections, and the Auxiliary Police Force helped with crowd control. The Alaska 49ers Citizens Band Radio Club also began a long association with the Walk this firs year. They patrolled the route in cars and provided communication links between the 12 rest stops along the route.

The first Walk was a tremendous success. Over 4,500 people walked, with more participating in volunteer capacities. Everything was in line to repeat the endeavor the following year. However, Halcro's high business profile in the community and his tenuous reputation surrounding the first Walk caused concern about how much of the money raised was reaching the proper destination—the children of Hope Cottage. Various articles and editorials again appeared in the local papers. People were upset, pointing out that vast amounts had been raised—$137,000—yet $80,000 remained sitting in the bank unused. Hope countered this accusation, noting that while the immediate goal of the first Walk was to resolve the extreme financial difficulties, the second goal was to raise enough money to build a proper facility, allowing the children removed from Dorbrandt and temporarily housed in API, to have a new, safe home. Also, this new home would allow other children currently in institutions Outside to return to Alaska.

The second Walk for Hope, while not such a blind undertaking, was nonetheless equally challenging and ultimately more successful. This year, the Walk celebrated over 11,000 walkers.

Anchorage's Walk for Hope turned 56 in 2025. Thousands of walkers and volunteers in Anchorage, Eagle River, MatSu Valley, and other hosting communities have participated over the years. And, since its inception, the Walk has earned proceeds for Hope on an average of $60,000 - $80,000 annually and over $4 million in total.

The Walk for Hope touched many communities around Alaska. A few of the communities who faithfully held walks for many years but have discontinued are Anchorage, Eagle River/Chugiak, Dillingham, Seward, the Matanuska-Susitna Valley, Naknek, South Naknek, and Willow, In Washington D.C., the offices of Alaska's congressional delegates have held an honorary Walk for Hope on Capital Hill in support of the Alaska Walks and Hope.

The First Board of Directors

When Nancy expanded Hope’s operations and incorporated as a nonprofit, she was required to establish a board of directors. In the beginning, her original board consisted of six community members. As Hope grew, Nancy expanded the board with professional, experienced, dedicated people who had also helped her along the way.

Sister Mary Clare, a member of the order of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, came to Anchorage in 1967. Her order, based in upstate New York, had long been respected for its work with children experiencing developmental disabilities. New York’s Archbishop Ryan sent her to Alaska to continue their work.

When she arrived in Alaska, Sr. Clare worked toward establishing a division of Catholic Charities in Anchorage. As the director of the division, and someone with a personal interest in working with children who experienced developmental disabilities, Sr. Clare eventually became involved with Nancy and Hope.

When Sr. Clare first arrived at Dorbrandt Cottage, she witnessed a room full of cribs and children. She thought Dorbrandt was a clean and home-like place and realized how well Nancy was caring for the children. But she also immediately recognized Nancy’s financial situation was dire and that she desperately needed additional support.

Reverend Norman Elliott had a similar reaction when meeting Nancy. Elliott was an Episcopal minister who lived in Nancy’s neighborhood. He lived in Ketchikan from 1958 until 1962, where he became involved with the Alaska Children and Adults Association. When he moved to Anchorage in 1962 he continued his affiliation with the association. Elliot met Nancy when she asked him to stop by on Sundays to meet informally with the children. When Nancy’s problems began, he stuck around.

John Molletti was the director of the Anchorage Baptist Church located in Rogers Park neighborhood. He was also in charge of a Baptist-run home for homeless children on Maplewood Street. Although he had long been involved with children, his work with Hope was his first experience with children who experience developmental disabilities.

Nancy knew she needed someone with financial expertise, so she invited her own banker, Fred Smith, the manager of the East Chester branch of First National Bank of Anchorage, to join the board. She knew he would be a valued addition and a willing participant because he had helped since Hope’s beginning. Smith had allowed them to finance a car, as well as other Hope needs, in their own name. Nancy acknowledged that without the support and generosity of Smith, Hope would have never survived. When the state was late in sending checks or reimbursing Nancy for expenses, she could always arrange a thirty-day loan to tide them over and meet payroll until the checks arrived. To round out the board, Nancy tapped into other professions to draw on a more practical knowledge. These members included Lee Robertson, a registered nurse, and Dr. Helen Whaley, who had pioneered work with people who experience developmental disabilities in Anchorage.

Finally, Nancy relied on local radio celebrity Herb Shaindlin, a friend and powerful community advocate, who would help to spread the message of Hope.

The Alaska Psychiatric Institute

With the new year and new decade of the seventies looming, Halcro faced a difficult situation. In addition to his proposed fundraisers, he also wanted to streamline costs by altering the lease situation on the Dorbrandt house. He did not think it was a cost-efficient rental property. Halcro attempted to break the lease by having the house inspected, knowing it would be hard for it to pass. Little did he anticipate what would happen once the inspectors arrived. They found several severe breaches of the fire code.

Thirteen children were living in the house by this time and all were non-ambulatory. In the event of a fire, they would have to be carried out. The fire chief immediately ruled the home uninhabitable, and the children had to be moved out. Unfortunately, the other homes Halcro tried to lease were also not acceptable for housing children with disabilities.

Halcro and the board were desperate. They managed to set up a deal with the Alaska Psychiatric Institute (API), which had space available in a basement wing. The director of API, Dr. Carl Koutsky, facilitated this temporary move. The children were transferred to API by the Anchorage Fire Department’s Rescue 49 ambulance and the Alaska Native Medical Center’s two-stretcher ambulance. Two trips were necessary to make the transfer. Beds and other equipment were labeled and transported to the hospital by API pickup trucks.

Six members of the Hope staff—three registered nurses, one licensed practical nurse, and two nurse’s aides—were accepted for temporary employment at API to work in the Hope wing.

Shortly after, Halcro announced the planned construction of Hope Park with funds generated by the upcoming Walk for Hope on lands donated by Anchorage Retarded Citizens Association (formerly ARCA, now The ARC of Anchorage). He stressed that this new building would only be for the children now at API. The other homes would remain part of Hope’s mission to keep children with developmental disabilities living in a regular neighborhood and participating in activities with other children in the community.

Building Hope Park

With Halcro’s fundraising success, Hope generated enough money to finance the building of Hope Park. The board hired a local architect to design a facility and began searching for a location. A contractor, Ray Kent, was hired to build the new home. Negotiations were made with ARCA, whose president, Marvin Frankel, had supported Nancy and Hope Cottage from the beginning. ARCA’s offices were just off Northern Lights Boulevard, on land allocated by the Department of Mental Health. ARCA agreed to lease part of the land to Hope for one dollar.

With so much happening, the board realized they needed to hire someone to manage Hope and the building of Hope Park. Kent, the contractor, was asked to be the executive director, which he accepted. Kent did not have experience in the field of developmental disabilities, but he did have practical building and organizational experience.

Hope Park was completed in October 1971. Kent knew its completion was a symbol of an Alaska community achievement, and he decided to celebrate. Kent organized a grand opening ceremony, inviting community leaders to witness Hope’s accomplishment. He even invited President Richard Nixon to perform the ribbon cutting ceremony. In the end, Alaska’s Lieutenant Governor H. Red Boucher officiated.

The Hope Park facility was not without its faults. No one guiding its internal design had any background in the day-to-day needs of individuals with physical and developmental disabilities. Eventually, years later when it was affordable, there were necessary internal and external renovations done to adapt to both the aging of the individuals who lived there and the licensing requirements for the new source of funding called Intermediate Care Facilities for the Mentally Retarded.

The 13 children who temporarily lived at Alaska Psychiatric Institute were transported to their new home, Hope Park, in ambulances provided by the Anchorage Fire Department and the Alaska Native Medical Center.

Foster Grandparent Program

The Foster Grandparent Program is federally funded and provides a small stipend to seniors, both men and women, who work part-time for supported nonprofit agencies. At Hope, these grandparents were partially in charge of the children in the Hope Park home. The program was lovingly referred to as a type of “mutual stimulation” because the seniors and the children provided love and stimulation for each other. Grandma Roberts, left, was the first foster grandparent to visit the children. She spent over five years volunteering in the program.

Specialized Foster Care Program

Hope started its Specialized Foster Care program in 1976, taking the extra step to offer children a family environment. At the time, the state’s foster program was not placing many children in foster care. The children who were placed in foster homes – three percent or less – wound up moving from home to home because families were not trained or qualified to handle the needs, behaviors, and medical issues of children with developmental disabilities.

Hope’s concept was simple. Foster homes that were prepared for the challenges would be more successful. So, Hope worked closely with the state for foster care licensing and worked with its staff for training in procedures and regulations. Hope was also responsible for the specialized training of the foster family. With this new direction, Hope eventually became qualified to do its own licensing, placement, and follow-up monitoring of its foster care program.

Since Hope expanded beyond a single home and growth was ongoing, the name Hope Cottage officially changed to Hope Cottages in 1977.

Roger Weed and Bob Cadieux

Roger Weed followed Kent as Executive Director. He brought experience in the social services profession, a first for the agency. Prior to joining Hope as its first deputy director under Kent's executive directorship in the summer of 1975, Roger was a juvenil and rehabilitation counselor at the Langdon Clinic in Anchorage. He was a past president of the Alaska Chapter of the National Rehabilitation Association and a member of the governor's advisory board for Hire the Handicappted. He also held a teaching position at the University of Alaska.

In 1977, Robert Cadieux, a local businessman, became board president. Cadieux moved to Anchorage in 1968 and started his own investment company. He was instantly interested in Hope's mission and, almost immediately upon joining the board, took over as president.

Weed's experience in the social services field and Cadieux's sensitivity and strong business sense helped turn Hope into a stable, professional organization.

Cadieux made several major contributions during his tenure. His first goal was to have a broader cross section of expertise on the board, including people with backgrounds in health and disabilities. He is perhaps best remembered for his ability to organize and streamline how the board run. Strictly following "Robert's Rules of Order," Cadieux established committees and expected concise reports at the monthly meetings. Much of his board organization continues today.

Although not the level of crisis in former years, a major issue Cadieux contended with was financial need. To garner financial support, Cadieux and other board members traveled to Juneau, put together proposals, and won contacts to help Hope.

Fundraising was another area of financial development. In 1977, Corbett Mothe was transferred to the newly created position of Director of Public Relations and Fundraising. He assumed leadership of the Walk for Hope and was charged with developing new fundraising endeavors and building community relations. From the very beginning, Mothe established a policy of positive public relations. Individuals would always be portrayed for their abilities, not disabilities. Handicappist marketing was never allowed. During Mothe's 28-year tenure, the public relations and resources development position grew into a four-person, professional team that continues to spread Hope's mission through fundraising and community outreach.

During Cadieux's eight-year tenure on the board, the agency evolved from a losely knit volunteer organization to a staff of professionals. No longer was survival based from paycheck to paycheck; there was now a $5 million budget.

Normalization as an Integral Part of Hope's Philosophy

During his time at Hope, Weed met with experts in the mental health field and visited other well-regarded national facilities. When viewing these facilities, Weed kept in mind the work of Dr. Wolf Wolfensburger, a pioneer in the mental health field. Wolfensburger had written a book, The Principles of Normalization in Human Services, on the concept of normalization. The book outlined the concept of normalizing—or de-institutionalizing—policies regarding people with developmental disabilities.

Wolfensburger's book developed an approach to working with individuals who are developmentally disabled through the concept of normalization. He said historically, society treated people with developmental disabilities as deviants, categorizing them as subhuman, menacing, pitiable, sick, burdensome, ridiculous, childlike, or a holy innocent. He also said that through the latter half of the nineteenth century, individuals with disabilities were segregated and institutionalized. Woflensburger concluded it was time to redefine these theories and provide individuals with developmental disabilities with normal living situations.

Weed met Woflensburger at a conference in Anchorage in 1976. He remembered Wolfensburger pointing out that most facilities looked like warehouses and a graveyard was always nearby. Soon after, Weed drove to the property Hope secured to build a enw facility, and sure enough, passed by a graveyard. This experience made him aware of how ingrained certain aspects of institutionalization were in people's minds. After that, he strove to move away from institutionalization and to create more home-like atmospheres, incorporating learning programs and hiring live-in teaching staff rather than custodial staff.

With normalization as a guide, larger group homes were dispensed into smaller groups of four people with a live-in staff, which Hope believed created a more normal living environment.

Preparing for a New Decade

When Roger Weed left Hope in 1978, the executive director position was left vacant for almost six months. Dr. Bob Morgan, a clinical psychologist who was familiar with Hope and whose services had previously been contracted by Hope, stepped in while the board searched for a new executive director. The board sought a person with strong managerial expertise to organize Hope internally, refine program services, and prepare the agency for further expansion.

In May 1979, Roger VanWagoner, "a hotshot from Outside," as people remember him, became Executive Director. He made his public debut that June at the groundbreaking for the two new 10-bed homes—Hope and Forest. VanWagoner signed a two-year contract to be executive director. VanWagoner began his career working with juvenile delinquents, but he shifted his focus to developmental disabilities. He had previously been director of Johnson County Mental Retardation Center in Kansas City, Missouri, and prior to Hope, had been the executive director of North Central Human Services, Inc., a non-profit corporation for the developmentally disabled in Forest City, Iowa.

Although VanWagoner had been involved in both educational and residential services when he was at North Central, he did not plan to expand Hope beyond its residential scope. The board hired him for the main purpose of organizing and streamlining the day-to-day management of the ever-expanding and increasiongly professional agency.

VanWagoner's goal was a period of stabilization for the agency after six months without a director. He proved to be very effective in organization, and by the time he left he had set Hope on the right course for the 1980s.

Strides continued to be made in the innovative and creative approach to providing services to Alaskans with developmental disabilities during the 1970s. During the early part of the decade, efforts were focused on constructing and leasing homes to accommodate both displaced adults and children from in and out of state. Over 80 Alaskans returned from institutions located out of state. Once this effort was underway, Hope began to re-introduce people to their families and homes.

The 1970s was a period of growth, not only for Hope and its operations, but also for Anchorage and Alaska. It was a time of immense wealth from oil ventures for the state and its citizens. In Anchorage, buildings were constructed all over the city, both commercial and residential, reflecting for the first time the skyline of a metropolis. But it was nothing compared to the growth in the 1980s.